Laika: The Little Dog Who Never Came Home 818

Sixty-seven years have passed since a stray dog from the streets of Moscow became the first living creature to orbit Earth. Her name was Laika. To the world, she was a symbol of progress, a marvel of science, a step into the future. But behind the headlines and history books lies a quieter truth: Laika was not a volunteer. She was a gentle, trusting animal who never chose to leave, who never knew why she was taken, and who never returned.

Her real name was Kudrjavka, meaning “curly” in Russian. To the handlers who trained her, she was known for her calm demeanor, her resilience, and her ability to adapt. These qualities, born of hardship, made her a prime candidate. Laika had survived the brutal Moscow streets, enduring cold, hunger, and uncertainty. And because of that, the Soviet scientists believed she would survive the confines of space better than others.

It was 1957, and the Space Race between the Soviet Union and the United States was accelerating. After the launch of Sputnik 1, Soviet leaders wanted another triumph, something bigger, more dramatic — a living passenger in orbit. There was no time to design a capsule for return. The mission was a statement of power, not a plan for survival.

Laika was selected.

On November 3, 1957, Sputnik 2 rose into the night sky with Laika inside. The capsule was equipped with food, water, oxygen, and padded walls — but no way back. From the start, it was never about bringing her home.

For decades, the details of her death were murky. At first, Soviet officials claimed she survived several days before succumbing peacefully. Later reports revealed a harsher truth: Laika likely died within hours from overheating and stress. Alone, frightened, and far from the streets she once knew, her short life in orbit ended quietly, her body left to circle Earth for months until Sputnik 2 burned up in April 1958.

In that time, her capsule orbited the planet 2,570 times. But she never touched ground again.

Laika became a symbol. To some, she represented the triumph of human ingenuity, the bold leap toward space exploration that would eventually carry cosmonauts and astronauts beyond Earth. To others, she represented the cost of ambition — a reminder that progress can be brutal when compassion is ignored.

She never asked to be a pioneer. She didn’t sign up to represent science or politics or the rivalry between superpowers. She was a small, trusting creature who wanted warmth, food, and affection. Instead, she became an icon of sacrifice.

That is why remembering Laika still matters.

Her story forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that not all progress is kind. It asks us to reflect on the choices we make in the pursuit of achievement — and on who, or what, pays the price. In Laika’s case, the price was a life cut short, taken not out of necessity but out of urgency to prove superiority.

Yet from her tragedy came a shift in how we think. The backlash and grief that followed her death sparked conversations about ethics in science and the treatment of animals in research. Decades later, even some of the scientists involved expressed regret, admitting they had been rushed by political pressure and haunted by what they had done.

Laika’s legacy is not only in the history of space exploration but in the questions she left behind. Questions that remain relevant today: How do we balance ambition with responsibility? How do we ensure that progress does not come at the expense of compassion? And how do we measure the true cost of discovery?

Remembering Laika is not about erasing the achievements of the past. It is about honoring the life that made them possible — and acknowledging that breakthroughs should never be divorced from humanity.

Because in the end, Laika was not a symbol. She was a dog. A little stray with soft fur, curious eyes, and a heart that trusted. And while she became part of history, her story is also a reminder: progress should not be pursued without conscience.

Sixty-seven years later, as we continue to reach for the stars, her memory circles back to us like the orbit she once traveled. Laika reminds us that science must ask not only what can we do but also what should we do.

Her story endures because it is more than just the tale of the first dog in space. It is a reminder of the responsibility we carry — to those who cannot choose, to those who trust us, and to the future we are shaping.

Laika’s pawprints may be long gone from Earth, but her mark remains on our conscience.

And that, perhaps, is her true orbit: not around our planet, but within our hearts.

The Arctic Secret of Anger: What We Can Learn from the Inuit 138

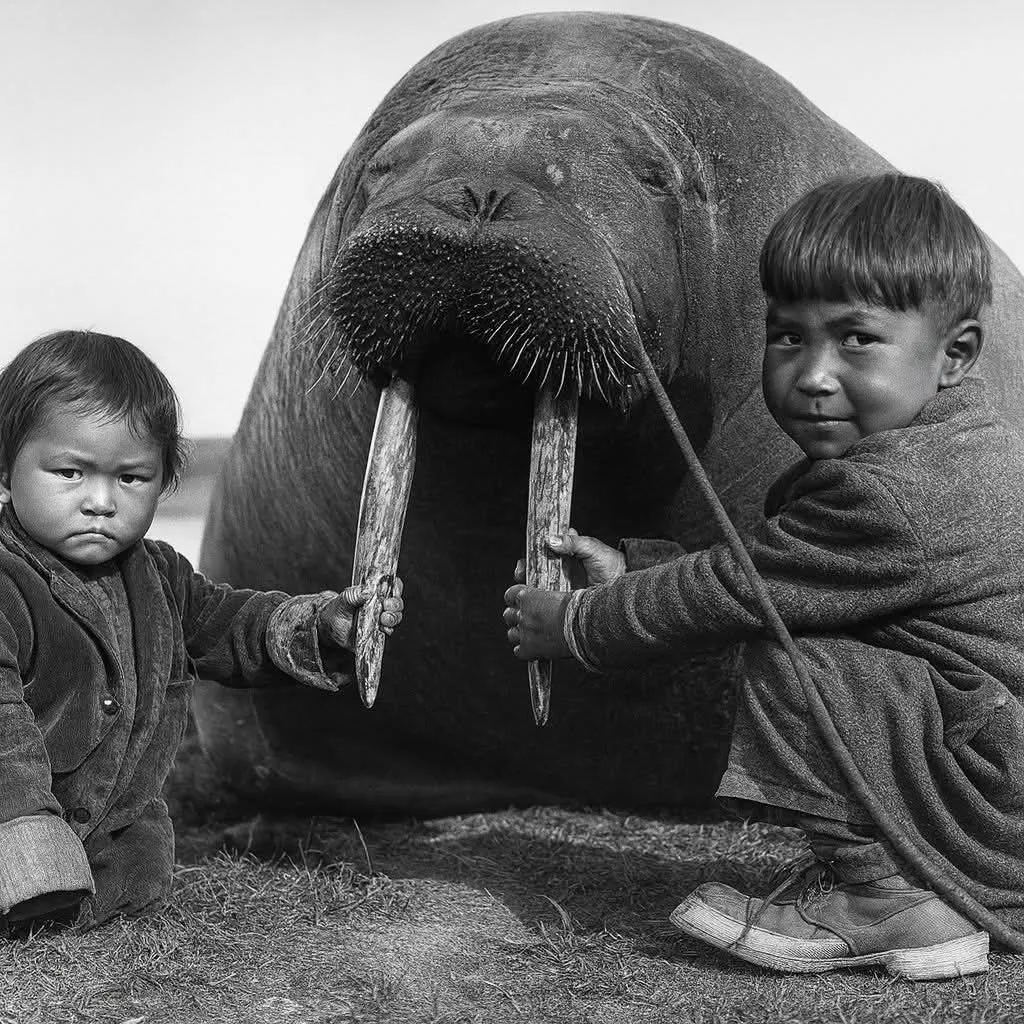

In the 1960s, Harvard graduate student Jean Briggs embarked on a journey that would challenge everything she thought she knew about human emotion. At 34, she traveled beyond the Arctic Circle to live in the unforgiving tundra for 17 months. There were no roads, no heating, no grocery stores—and winters plunged below –40°C.

To truly understand the community, Briggs convinced an Inuit family to “adopt” her. Living alongside them, she observed life in its natural rhythm, from dawn to the endless twilight of the Arctic winter. It was during this immersion that she noticed something extraordinary: the Inuit adults rarely, if ever, displayed anger. They never shouted, never scolded, never blamed.

One day, a boiling kettle spilled inside an igloo, damaging the ice floor. Briggs expected shouting or at least frustration—but all she heard was a calm, “Too bad,” before another kettle was fetched. Another time, a carefully woven fishing line snapped on its first cast. The response? A matter-of-fact, “Let’s make another one.”

Next to them, Briggs felt impulsive, childish, even reckless. She began asking herself how Inuit parents taught their children such mastery over emotion. One afternoon, the answer became clear. A young mother was playing with her furious two-year-old son. She handed him a small stone and said, “Hit me with it. Again. Harder.”

The boy threw the stone. She covered her eyes and pretended to cry, letting out a soft, “Ooooh, that hurts!” At first, Briggs found it strange—until she realized the depth of the lesson. Inuit parents never scold small children or respond to anger with anger. Instead, they turn conflict into gentle, instructive play, teaching empathy, patience, and self-control. Even when a child hits, bites, or lashes out, the adult responds calmly, showing that anger need not be met with anger.

Briggs witnessed an emotional intelligence that seemed almost superhuman—a culture where anger is not feared, but understood. It isn’t suppressed or ignored; it is acknowledged, guided, and transformed into empathy.

In a world where rage often escalates, where shouting seems the natural response to frustration, the Inuit offer a radical alternative. Through patience, play, and example, they teach that self-control is not a rigid rule but a skill nurtured with love and understanding.

Perhaps, as Briggs discovered in the silent, icy Arctic, the key isn’t to eradicate anger, but to recognize it, respect it, and teach the next generation to respond with calm. In a small igloo, with a tiny stone and a pretending tear, Briggs saw the future of emotional intelligence—and it started not with punishment, but with play.